Last week, we explored the difference between AI that replaces human capability and AI that amplifies it. We looked at principles such as preserving human agency, maintaining human judgment, facilitating connection, and embedding human values from the start. These principles matter because they influence whether AI serves human flourishing or quietly undermines it. Principles, however, remain abstract until seen in practice. This week turns to concrete examples of AI amplifying human capability, solving problems that resisted previous solutions, and enabling possibilities that did not exist before. These are not speculative scenarios or glossy demos; they are documented, real-world systems already in use, showing both the successes and the human judgment that makes them work. After the 2019-2020 Australian bushfires burned about 73,000 square miles and affected nearly 3 billion animals, conservationists faced a daunting question: where, and how well, was nature recovering? They needed to know which species were returning, in what numbers, and in which landscapes, so they could target limited staff, funding, and protection measures where they would make the greatest difference. The standard tool was familiar: camera traps deployed across vast burned areas. Yet each camera generated tens of thousands of images, and each image had to be manually inspected and labelled. A single researcher might spend months on one site’s photos, while hundreds of other sites waited in line. By the time the data reached decision-makers, it was often outdated.Wildlife conservation: Eyes on recovery

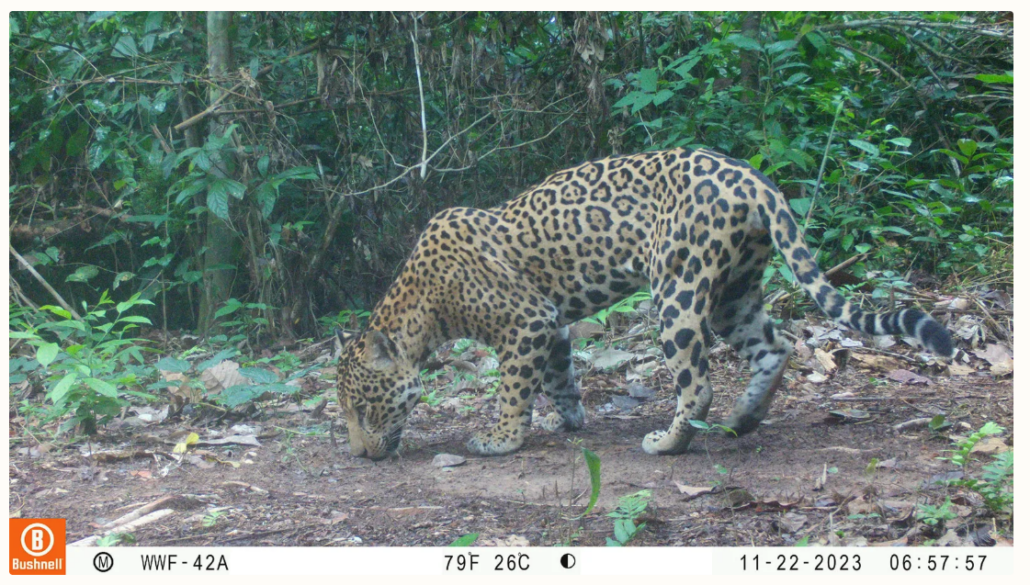

WWF and partners worked with Google on Wildlife Insights, an AI-powered platform that can identify over 1,300 species globally and more than 150 Australian species, and process millions of images in a fraction of the time of human researchers. In the post-bushfire recovery work, the system helped detect over 150 species returning to burned habitats, including endangered greater gliders, providing early signs of where ecosystems were rebounding and where more help was needed.

Crucially, the AI does not decide which areas get protected or which species to prioritise. Rangers, ecologists, and local communities still make those decisions. The system simply removes the data bottleneck that used to slow them down, turning months of repetitive image triage into hours and freeing experts to spend their time in the field and in deliberation rather than at a screen. What makes this approach particularly promising is its openness and community focus. Wildlife Insights is accessible to conservation organisations worldwide, including those that could never afford bespoke AI systems. Humans remain central to every conservation decision; AI serves as infrastructure that clears the way for faster, better-informed human action.

When Hurricanes Helene and Milton hit North Carolina and Florida in 2024, they left behind flooded homes, destroyed infrastructure, and communities facing months or years of rebuilding. The destruction did not fall evenly. Some neighbourhoods combined severe damage with high poverty and weak safety nets, meaning those hit hardest had the least capacity to recover.

GiveDirectly, a nonprofit that provides direct cash support to people in crisis, confronted a familiar challenge in humanitarian diplomacy: how to identify the most vulnerable households quickly enough to reach them during the critical early days after a disaster. Traditional needs assessments like door-to-door surveys, paper forms, and manual verification are slow and labour-intensive. They deliver accurate information, but too late.

In response, GiveDirectly partnered with Google to analyse satellite imagery of affected areas using AI, comparing before-and-after images to identify the areas with the most significant damage. They then combined this with socioeconomic data to locate neighbourhoods where severe physical damage intersected with high economic vulnerability. Within days, the organisation could send USD 1,000 cash payments directly to households most likely to need urgent support, instead of waiting weeks for complete assessments.

The critical decisions in this process remained human. People within GiveDirectly defined the criteria for ‘most vulnerable’, determined how to balance speed with caution, and validated the outputs before sending money. The AI did what no group of staff could do in the same timeframe: scan thousands of square miles of imagery, flag probable damage, and cross-reference it with other indicators.

What gives this story its ethical weight is not just the sophistication of the tools but the clarity of the humanitarian purpose. The technology is explicitly designed to help those in greatest need first, under human oversight and accountability. AI does not decide who is worthy; it accelerates the process of learning where human help is most urgently required.

Nheengatu was once a lingua franca of the Amazon, widely spoken across the region from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Colonial violence, forced assimilation, and linguistic suppression nearly extinguished it. Today, estimates suggest around 20,000 speakers across Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela, and UNESCO classifies Nheengatu as ‘severely endangered’.

Endangerment is not only about numbers. A language with thousands of speakers can still be at risk if it is difficult to use in public institutions, in schools, or in digital spaces. For Nheengatu speakers, there have been no spell-checkers, no predictive text, and few digital tools to make writing in Nheengatu as convenient as writing in Portuguese or English.

IBM researchers, in collaboration with the University of São Paulo and, most importantly, with Nheengatu-speaking communities, have developed AI-based tools to support the language. These include translation systems that work between Nheengatu, Portuguese, and English, as well as writing aids such as spell-checking and suggestion tools, which are beginning to be used in schools where Nheengatu is taught.’

Here, the way the project is governed matters as much as the technology itself. Indigenous communities lead the effort, retain control over linguistic data, and set boundaries on what is collected and how it is used. The AI does not impose outside grammatical structures or extract data for unrelated purposes; it exists to remove practical barriers that make Indigenous languages harder to use online. The result is not a machine that ‘saves’ Nheengatu, but infrastructure that helps young people use it more easily in the digital spaces where their lives increasingly unfold. It is a case where AI amplifies community-driven revitalisation, respecting sovereignty while providing tools that dominant languages take for granted.

For many small business owners, the biggest challenge is not vision but capacity. Someone running a family coffee roasting business, a small design studio, or a local consulting firm often has to be strategist, marketer, analyst, and customer support all at once. High-quality market research, tailored analytics, or professionally managed campaigns have traditionally required budgets and staff that microbusinesses simply do not have.

Recent surveys suggest that a growing share of micro and small businesses are turning to AI tools to address these gaps precisely, using them for tasks such as drafting marketing content, analysing sales data, and automating routine communication. The tools do not provide genius-level insight, but they do offer a baseline level of capability that previously required external agencies or dedicated staff.

Consider Henry’s House of Coffee, a family-owned roastery in the United States, which uses AI to draft newsletters and social media posts, cluster customer feedback into themes, and forecast inventory needs based on historical data and seasonal patterns. This is one of many small businesses using AI in this way: the owner still decides which stories to tell, what the brand stands for, and which customers to prioritise, while AI generates drafts, surfaces patterns, and automates repetitive tasks that the human owner ultimately filters, corrects, and chooses to implement.

This pattern matters beyond individual businesses. When only large corporations can access sophisticated tools, competitive advantage tends to concentrate with those already powerful. When AI tools become affordable and usable for very small firms, competition can shift toward the quality of ideas, relationships, and execution rather than simply the size of the balance sheet. AI, deployed in this way, can help narrow some structural gaps rather than widen them.

Smallholder farmers in countries like Malawi, Ghana, Kenya, and others have long faced a different kind of bottleneck: the distance between expertise and the field. Government agricultural extension officers may possess valuable knowledge, but a farmer cultivating a few acres might have to travel for hours or days to reach them, losing work time and spending money in the process. In many cases, advice arrives too late or never at all.

AI-powered services such as FarmerAI and Farmerline’s Darli AI attempt to bridge this gap by meeting farmers where they already are, on their phones, using familiar tools like WhatsApp or simple voice calls. Darli AI, for instance, has been recognised by Time magazine as one of the best inventions of 2024 and can interact in over 27 languages, including African languages such as Twi, Swahili, and Yoruba.

These systems allow farmers to ask questions about pests, soil management, crop rotation, or market access and receive tailored responses that reflect local conditions. The underlying knowledge comes from agronomists and extension officers; AI organises and delivers it at scale, making it accessible at any time, without travel, and in languages farmers actually use at home.

Again, the farmers themselves remain decision-makers. They weigh the advice against their experience, their land, and their risk tolerance. Extension workers can also use the tools to reach more farmers, rather than being replaced by them. Here, AI addresses not only technical constraints but also structural inequalities in who can easily access expert knowledge.

Across these domains (conservation, disaster response, language preservation, small business, and agriculture), technologies and contexts differ, but the underlying patterns are remarkably consistent. In each case, humans retain agency and responsibility over important decisions. Conservationists set protection strategies and trade-offs. Humanitarian organisations determine the criteria for aid. Indigenous communities control how their languages are used and digitised. Business owners define their brands and relationships. Farmers decide what to do with their land. AI is powerful, but it is not in charge.

In each case, AI is applied to remove specific constraints that prevent people from doing what they already want to do: data bottlenecks, distance, a lack of tools in minority languages, and resource limitations. It democratises access to capabilities by making sophisticated tools available to smaller organisations, marginalised communities, and individuals who were previously excluded.

And in each case, human values are clearly articulated and used to guide the design and deployment of systems. Conservation systems aim at ecological recovery, not mere surveillance. Disaster systems prioritise the most vulnerable, not administrative convenience. Language tools respect data sovereignty rather than extracting resources. Business and agricultural tools seek empowerment rather than dependency.

The future of AI and humanity is being shaped right now, not only in international negotiations or corporate boardrooms, but in thousands of specific design decisions and deployments. Each project sets precedents for what is considered normal or acceptable: who is consulted, who benefits, who bears risk, and who retains control.

The examples here represent choices that favoured amplification over replacement, human agency over algorithmic dominance, and democratisation over concentration. Different options, such as automating conservation decisions, centralising linguistic data without community consent, restricting advanced tools to large corporations, or locking farmers into opaque systems, were all possible. They were not taken.

When anxiety about AI’s impact surfaces, these stories offer more than comfort; they offer templates. They invite policymakers, technologists, communities, and users to insist that new systems follow similar patterns: centring human judgment, aligning with articulated values, and widening access to capabilities rather than narrowing it. The future is not predetermined, and the trajectory of AI and humanity is still being shaped by the choices we make now. The question is which patterns become the default, and which remain exceptions we admire from afar.

Author: Slobodan Kovrlija