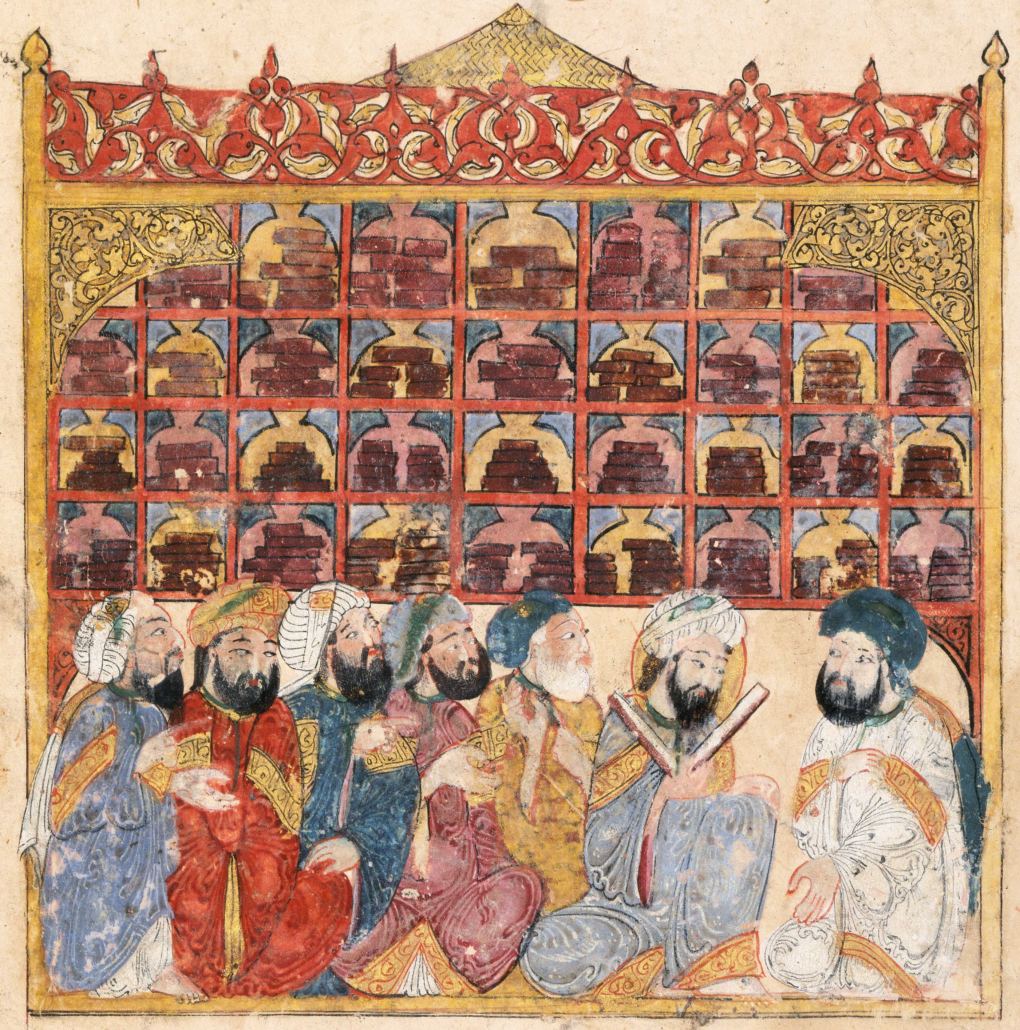

Ahead of Diplo’s visit to the Gulf region, and while still reflecting on the impressions from the AI, Governance and Philosophy – A Global Dialogue, namely the fact that no single cultural milieu contains all the answers needed for a just and humane future shaped by AI, I began exploring what may be the insights provided by the Arabic philosophical traditions. In earlier reflections on Chinese thought and AI, I emphasised how philosophical traditions shape both the development of technology and its cultural acceptance, and how governance must engage not only with technical systems but with the deeper transmission of values. The Arabic philosophical tradition that flourished during the Islamic golden age offers insights that remain highly relevant for contemporary AI development, policy, and governance. AI is often presented as a novel challenge without precedent. Yet, many of the philosophical dilemmas we face today – questions of agency, justice, accountability, and the purpose of knowledge – have been explored in depth by earlier intellectual traditions, including Arabic thinkers. In his blog Early origins of AI in Islamic and Arab thinking traditions, Dr Kurbalija argues that many concepts at the base of what we today call ‘AI’(algorithms, statistical thinking, pattern, classification) have precursors in that tradition, emphasising how those traditions saw the role of reason in balancing revelation and ethics. The term Islamic golden age refers to the network of scholars from the 8th to the 13th centuries, centred in Baghdad but connected across the Islamic world, who worked in philosophy, mathematics, medicine, theology, and literature, often translating and integrating Greek, Persian, and Indian sources. In this blog, I’ll focus on four scholars, often described as the key thinkers of this tradition, in chronological order.Arabic philosophy in the context of AI governance

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (872–950), or just Al-Farabi, often called the ‘Second Teacher’ after Aristotle, perceived society as an organism guided by a virtuous leader whose role was to orient collective life towards the highest good. For Al-Farabi, knowledge and governance were inseparable: political leadership had to be grounded in ethical purpose and rational deliberation. This resonates almost completely with the role of the Emperor in Chinese philosophical and political thought.

For AI governance, this translates into the principle that governance structures cannot be purely procedural or technical. They must be evaluated by their capacity to ensure that AI serves human flourishing. Al-Farabi’s vision of the virtuous polity suggests that global AI governance should not limit itself to risk management but focus towards positive ends – justice, education, and the well-being of communities.

Ibn Sina (980–1037), better known in the West as Avicenna, systematised Aristotelian philosophy and developed sophisticated theories of logic, metaphysics, and epistemology. He placed strong emphasis on the faculties of the human mind, particularly reason, as the means by which knowledge is organised and meaning is discerned. His extensive work on categorisation and classification resonates with contemporary AI systems, which rely on taxonomies, ontologies, and pattern recognition.

The relevance for governance lies in two areas. First, Ibn Sina’s insistence that knowledge must be integrated into a broader metaphysical framework suggests that technical systems should be evaluated for alignment with ethical and human-centred goals rather than only for accuracy. Second, his defence of human rational agency underscores that AI should not erode human responsibility and that governance must preserve the principle that humans are the ultimate arbiters of meaning and accountability, not machines.

Al-Ghazzali (1058–1111), theologian, jurist, and mystic, is best known for his critique of excessive rationalism in The Incoherence of the Philosophers, arguing that reason, as valuable as it is, could not answer all metaphysical or ethical questions. For him, ethical life required humility, spiritual discipline, and recognition of human limitations.

This perspective is especially useful when thinking about AI as a tool that promises predictive power and optimisation. Al-Ghazzali’s emphasis on limits cautions against the illusion of total control through technology, suggesting governance frameworks that would benefit from recognising uncertainty, fallibility, and the potential for unintended consequences. In modern terms, this implies governance structures that mandate caution, review, and adaptive regulation rather than blind trust in algorithmic outputs.

Ibn Rushd (1126–1198) defended rational philosophy against Al-Ghazzali’s critique, arguing that truth could be reached through both revelation and rational inquiry. He was also a great commentator on Aristotle, insisting that philosophical reasoning was universal and not confined to any one cultural or religious tradition.

For global AI governance, Ibn Rushd’s commitment to universality and dialogue is crucial. It underscores that AI cannot be governed by a single normative framework. Instead, it requires intercultural dialogue where diverse traditions contribute to a shared search for principles of justice, accountability, and dignity. This aligns with what I have previously described as the need for inclusive governance rooted in universal values articulated through plural traditions in the Inclusive AI governance: Universal values in a pluralistic world blog.

Taken together, these thinkers provide several governance principles:

These principles resonate with parallel insights from Chinese and Western traditions: harmony and balance in Chinese philosophy, and virtue and rational deliberation in Western thought.

The Arabic philosophical tradition gives us not only historical continuity but active resources: wisdom, reason, balance, moral ends, pluralism, transmission, and dialogue. If global AI governance embeds these, we stand a better chance of creating AI systems and policies that are human-centred, just, and trusted.

In crafting any global multistakeholder AI governance policy, I believe we should:

In doing so, we move closer to a principle which sounds like common sense, but is often overlooked as we need wisdom more than mere knowledge to ground technology in what truly matters.