Deepfakes remain one of the most disruptive and unsettling AI developments of 2025. Hyper-realistic voice cloning and multimodal scams are now actively fueling fraud while eroding trust in media, institutions, and digital communication. Reports across cybersecurity and financial sectors indicate a sharp rise in deepfake-enabled incidents this year, with multi-million-dollar losses already documented. What began as a niche curiosity, best known for face swaps in online videos, has evolved into a powerful ecosystem of tools capable of generating convincing voices, faces, and entire multimodal personas. Today’s deepfakes are no longer only impressive demonstrations. They are operational, scalable, and continuously weaponized for fraud, manipulation, and disinformation. In some documented cases, just a few seconds of publicly available audio drawn from interviews, podcasts, or social media, were enough to clone a voice and trigger high-value financial transactions. The speed at which these attacks can be executed exposes a deeper issue: many digital systems still assume that seeing and hearing are reliable indicators of truth. Beyond financial crime, the implications extend into journalism, diplomacy, and democratic processes. When audio or video evidence can be fabricated with minimal effort, trust itself becomes a contested resource. The question is no longer whether deepfakes will spread, but whether societies can adapt fast enough to contain the damage they cause. The current deepfake wave is driven by several converging technical breakthroughs.How can societies respond to synthetic deception?

The technology behind the threat

This matters because trust is rarely compromised by a single piece of manipulated media. It becomes more difficult to verify authenticity when multiple channels (voice, video, text) are all coordinated to create a consistent, convincing message.

The most visible impact of deepfakes in 2025 has been financial fraud. Executive impersonation scams, sometimes called ‘CEO fraud’, have become more sophisticated and more dangerous. In several documented cases, employees authorized urgent wire transfers after receiving voice calls that sounded exactly like their superiors, complete with familiar speech patterns and contextual knowledge. The attack does not exploit technological ignorance so much as organizational psychology: urgency, authority, and fear of delay.

What makes these attacks particularly effective is that they target processes, not individuals. Many corporate safeguards assume that voice confirmation adds a layer of security. Deepfakes invert that assumption, turning verification into a vulnerability.

Political and geopolitical risks are harder to quantify but potentially more destabilizing. Synthetic videos of public figures making inflammatory statements can spread globally within minutes, long before fact-checkers or official channels respond. Even when debunked quickly, such content can shape narratives, polarize audiences, and leave lasting impressions. In high-tension environments like elections, protests, diplomatic crises, the damage may already be done before the truth catches up. Fabrication can be executed in minutes and distributed widely online, while verifying the authenticity of a deepfake often requires time-consuming technical analysis or corroborating evidence.

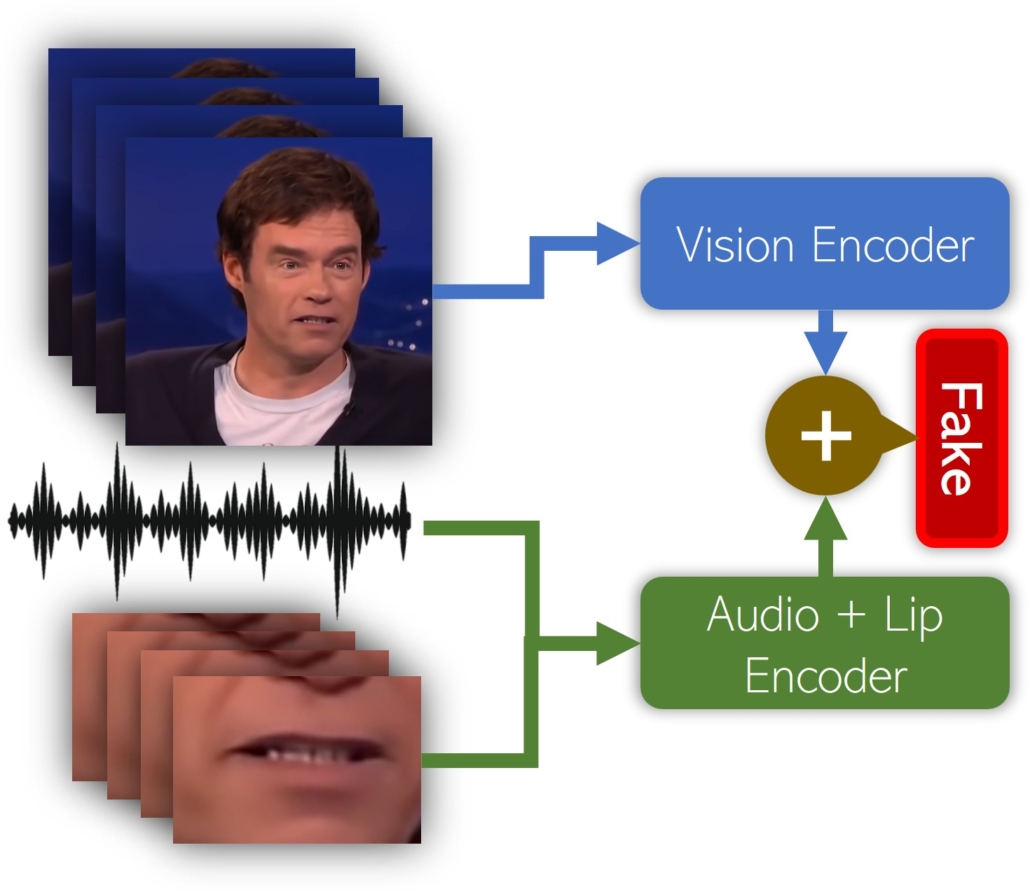

In response, a growing ecosystem of detection tools has emerged. These systems analyze micro-expressions, eye movements, lighting inconsistencies, and audio anomalies such as unnatural breathing patterns or phase irregularities. Some platforms are experimenting with cryptographic watermarks embedded directly into AI-generated content, while others focus on forensic analysis after the fact.

There has been real progress. Multi-layered detection pipelines are more effective than any single method, and platform-level interventions can slow the spread of synthetic media when properly deployed.

Yet the limits are becoming clear. Detection remains probabilistic, not definitive. High-quality deepfakes can evade many current tools, especially when compressed, cropped, or deliberately degraded for social media. Multiple studies suggest that even trained observers struggle to reliably identify sophisticated deepfakes, with accuracy often barely exceeding chance under realistic conditions.

The deeper problem is structural: generation scales faster than detection. Producing a convincing fake is becoming cheaper and more accessible, while robust detection requires constant retraining, computational resources, and access to original data that may not exist. This asymmetry means detection alone cannot be the foundation of trust.

Calls for regulation are understandable, but policy has inherent limitations in this space. Deepfakes evolve faster than legal frameworks, and enforcement struggles across borders. More importantly, regulation tends to focus on content classification, what is allowed or prohibited, rather than on the underlying erosion of trust.

The ethical problem with deepfakes isn’t just that they trick people, but that they make it hard to know what’s real at all. If any audio or video clip could be fake, people can deny real evidence just as easily as false content is spread. Genuine recordings lose credibility, and it becomes harder to hold anyone accountable for their actions.

This effect, sometimes called the ‘liar’s dividend’, is already showing up in public discourse. The existence of deepfakes alone makes it easier for people to dismiss inconvenient or politically damaging evidence as fake, even when it’s real.

We can’t leave all the responsibility on individuals to ‘be more skeptical’. Humans naturally trust what they see and hear, and it’s unrealistic to expect everyone to be constantly on guard against synthetic deception. The burden has to be shared across technology, institutions, and society.

If detection alone isn’t enough and regulation often lags, where should the response come from? Increasingly, experts point to provenance rather than perception, focusing on the source and chain of custody of media rather than just trying to judge whether the content looks real.

This can include practical tools like cryptographic signing of videos or audio at the moment they are created, secure metadata that records when and how content was produced, and verifiable audit trails that stay intact even if the files are copied or compressed. These systems don’t stop deepfakes from being made, but they give genuine content a clear signal of authenticity. In other words, unverified material isn’t automatically false, but verified media can carry extra trust in high-stakes situations like journalism, court evidence, or diplomatic communications.

Organizations also need to rethink workflows that assume everything they see or hear is real. High-risk decisions, such as financial transfers, urgent operational choices, or public announcements, should require multi-factor verification that doesn’t rely solely on voice or video. This isn’t just a tech problem; it’s a socio-technical challenge, requiring systems and processes to adapt to a world where identity signals can be forged.

Deepfakes force an uncomfortable reassessment of how trust works online. For decades, digital technologies expanded access to information while relying on assumptions carried over from the analog world in which recorded audio and video generally reflected real events and real people. Advances in AI have exposed how fragile those assumptions are, and how easily they can be exploited.

The challenge ahead is not to eliminate deception altogether. History shows that this is unrealistic. The goal is to limit how much damage it can cause. Doing so requires more than better detection tools. It calls for technical systems that give genuine content a clear signal of authenticity, ethical norms that discourage irresponsible use of generative AI, and institutions that are resilient when uncertainty arises rather than paralyzed by it.

If seeing and hearing are no longer enough to establish truth, societies must decide what replaces them. The deepfake challenge is ultimately less about artificial intelligence itself and more about whether human systems can adapt to a new reality. Trust will not be preserved through perfect detection or regulation alone. It will depend on shared effort. Technologists need to build provenance into how content is created. Institutions need to update how they verify information and make decisions. And citizens need to learn how to question content carefully without assuming that everything is fake. The foundations of credibility will not rebuild themselves, but they can be rebuilt if responsibility is shared across those who create, govern, and consume digital media.

Author: Slobodan Kovrlija