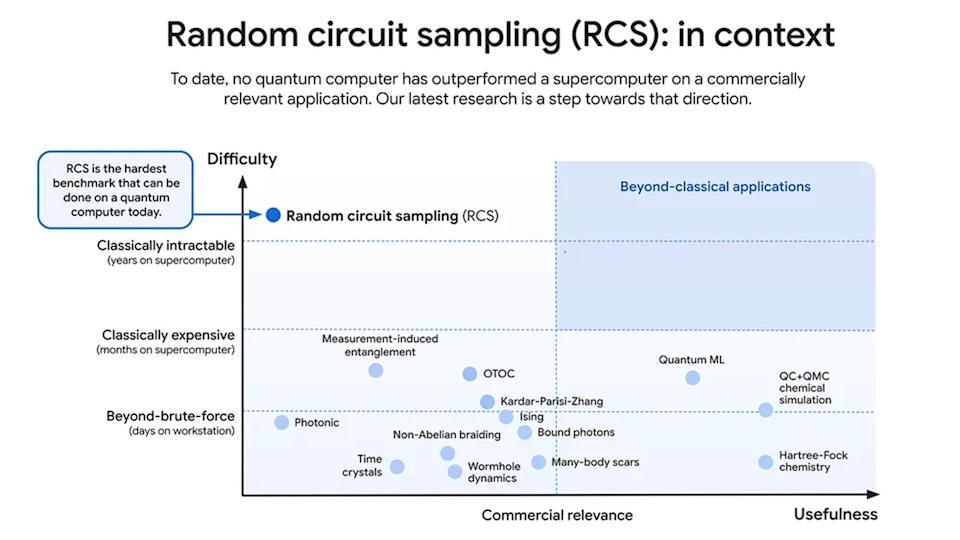

In late 2024, Google announced a result that immediately caught the attention of the scientific community: its new 105‑qubit quantum processor, known as Willow, completed a computation in a matter of minutes that would be effectively impossible for even the fastest classical supercomputers. The claim was not only that Willow was faster, but that it had crossed a qualitative boundary, performing a task that classical machines could not realistically complete at all. For Artificial Intelligence, this is a watershed moment. Unlike previous generations of noisy quantum chips, Willow achieved a below-threshold error rate, making it more reliable as it scales. This stability is the key to running Quantum Machine Learning (QLM) algorithms that can handle optimisation problems and massive datasets far beyond the reach of classical AI. Yet, this technological breakthrough has been accompanied by a more provocative narrative. Some commentators and a small number of physicists have suggested that quantum computers like Willow may owe their extraordinary performance to something far stranger than clever engineering: parallel universes. While this idea makes for an arresting headline, it also risks obscuring what Willow actually demonstrates and what it does not. Willow is a quantum processor built from 105 qubits, the quantum analogue of classical bits. Unlike bits, which exist as either a 0 or a 1, qubits can exist in superpositions of states and become entangled with one another. These properties allow quantum systems to represent and manipulate an exponentially large space of possibilities. The benchmark Willow was tested using random circuit sampling. In simple terms, the processor was asked to generate outputs from a highly complex and deeply entangled quantum circuit. This is a deliberately artificial problem, chosen not for practical usefulness but because it is extremely difficult to simulate on classical hardware. According to Google, Willow completed this task in under five minutes. Estimates suggest that simulating the same process on classical supercomputers would take longer than the universe has existed by many orders of magnitude. This is why the result is described as a strong example of quantum supremacy, the point at which a quantum system demonstrably outperforms classical machines on a specific task.What Willow actually achieved

Importantly, this does not mean Willow is already helpful for everyday computation. The benchmark is theoretical, and it does not directly translate into applications like optimization, chemistry, or cryptography. Its significance lies elsewhere: it shows that quantum hardware can now be built, controlled, and scaled to regimes that are genuinely inaccessible to classical computation.

Since Willow’s initial announcement, Google has continued to push beyond purely synthetic benchmarks. In 2025, researchers demonstrated an early algorithmic protocol called ‘Quantum Echoes‘ on Willow, designed to produce results that can be independently verified through physical experiments rather than inferred indirectly from complexity estimates. These demonstrations focus on simulating quantum systems themselves (an area where classical computers struggle fundamentally) and represent a subtle but important shift. While still narrow in scope, they suggest that quantum processors are beginning to move from abstract stress tests toward problems with direct scientific relevance, even if they remain far from general-purpose use.

Part of what makes Willow’s performance so unsettling is that it defies our everyday intuition about computation. Classical computers explore possibilities sequentially or through parallel hardware that still scales linearly with resources. Quantum computers, by contrast, operate in a space that grows exponentially with the number of qubits.

Each additional qubit roughly doubles the size of the system’s state space. Moving from 50 to 105 qubits is therefore not a modest improvement but a leap into an extremely larger computational regime. From the outside, the result can feel less like incremental progress and more like something qualitatively alien.

It is precisely this sense of alienness that opens the door to more speculative explanations.

Another reason Willow’s performance provokes such strong reactions is that quantum benchmarks scale in ways that feel disconnected from everyday technological progress. In classical computing, performance gains tend to be incremental and intuitive. In quantum systems, small increases in qubit count or fidelity can suddenly push a device into a regime where classical simulation collapses entirely. This abrupt transition from tractable to effectively impossible helps explain why claims of quantum advantage so often feel dramatic, even when they arise from carefully engineered laboratory experiments rather than radical new physical discoveries.

The idea that quantum computers might be exploiting parallel universes originates with the many‑worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, most prominently associated with physicist David Deutsch. In this interpretation, quantum events do not collapse into a single outcome when measured. Instead, all possible outcomes occur, each in its own branch of reality.

Applied to quantum computing, this leads to a striking image: when a quantum processor evaluates many possibilities at once, those possibilities might correspond to computations taking place across multiple parallel universes, with the final answer emerging in ours.

This interpretation is not logically inconsistent, and it is taken seriously by some researchers. However, it is crucial to note what it is and what it is not. The many‑worlds interpretation is a way of interpreting the mathematics of quantum mechanics. It does not make new testable predictions beyond those of standard quantum theory.

In other words, invoking parallel universes is not necessary to explain how Willow works.

Most physicists continue to work within more conservative frameworks, such as the Copenhagen interpretation, which treats quantum states as probabilistic descriptions rather than physically real branching worlds. From this perspective, quantum computers gain their power not by outsourcing work to other universes, but by carefully manipulating probability amplitudes and interference.

There are also more practical reasons for scepticism. One of them is historical perspective. Claims of quantum supremacy are not new, and earlier announcements have sometimes been softened or reinterpreted as classical simulation techniques improved. This does not invalidate newer results, but it does encourage caution. The meaningful question is not whether a particular benchmark can be declared won, but whether progress continues when benchmarks become more demanding and closer to real-world constraints. Willow’s achievement, impressive as it is, concerns a narrow benchmark designed to highlight quantum advantage. It does not yet solve problems of direct real‑world relevance. Scaling quantum systems from hundreds of qubits to the millions likely required for fault‑tolerant, general‑purpose quantum computing remains an open and formidable challenge.

Critics emphasise that quantum computing is still fragile, sensitive to noise, and dependent on sophisticated error‑correction schemes. Progress in these areas matters far more for the field’s future than philosophical debates about the multiverse.

None of this diminishes the importance of Willow. Benchmarks like random circuit sampling, though artificial, play a necessary role in the development of any new computing paradigm. They provide controlled environments in which engineers can test how error rates, coherence times, and entanglement behave as systems scale. Without such benchmarks, it would not be easy to distinguish genuine hardware progress from clever experimental tuning. In fact, its most meaningful contribution may lie in quieter technical details: improved stability, better error suppression, and evidence that larger quantum systems can be controlled more reliably than before. These advances are prerequisites for any future practical application of quantum computing.

The fascination with parallel universes says less about what Willow proves and more about how deeply quantum mechanics continues to challenge our intuitions. When a machine behaves in ways that strain our conceptual frameworks, it is tempting to reach for extraordinary explanations.

At present, Willow does not show that we are computing across multiple realities. What it shows is that quantum computers are steadily moving from theoretical curiosities to engineered systems with unprecedented capabilities. That alone is remarkable, and it is more than enough to justify the attention it has received.

The real story, at least for now, is not that reality is fracturing, but that our ability to build and control quantum machines is quietly, and measurably, improving.

Author: Slobodan Kovrlija