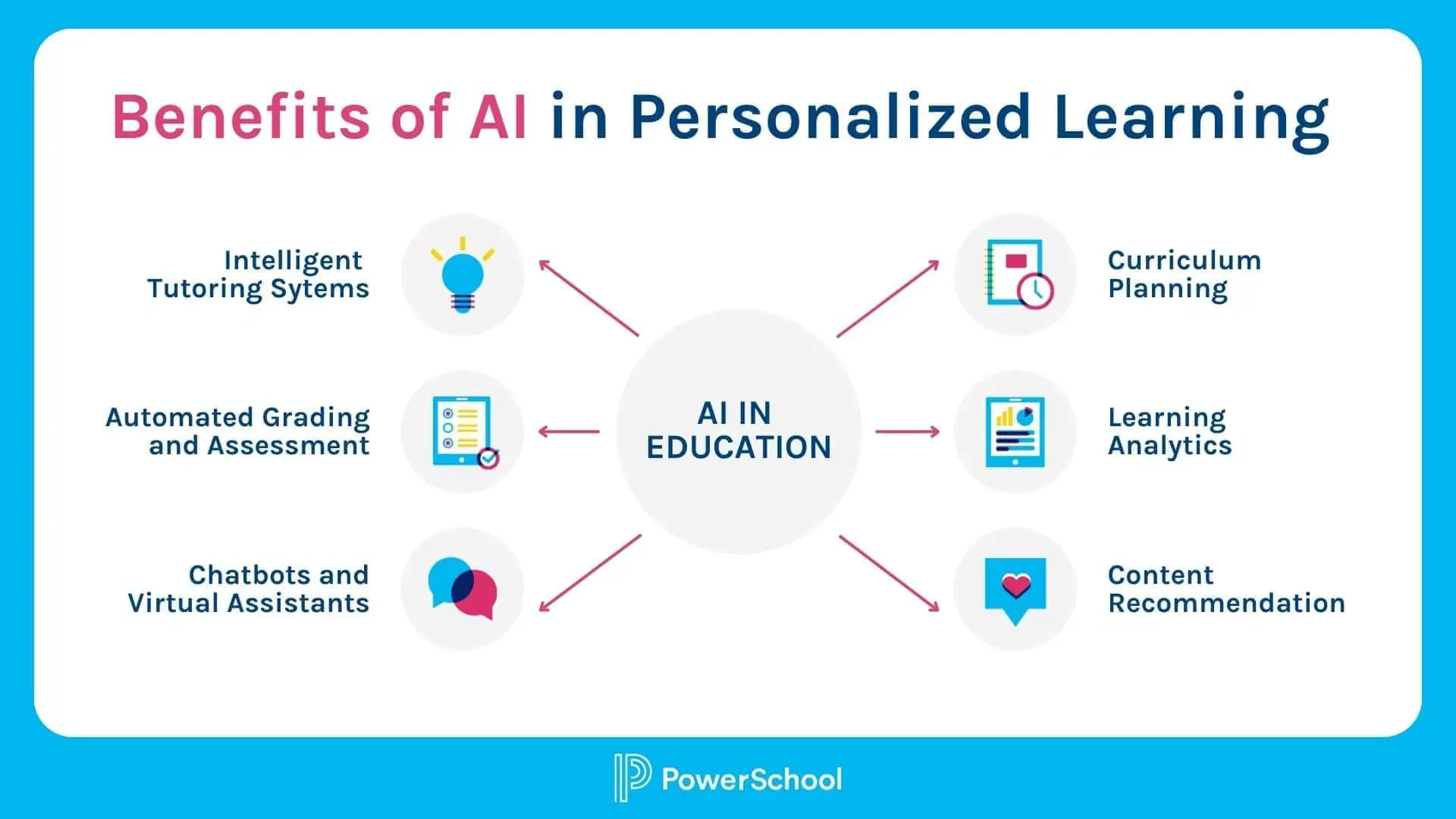

Adapting to AI requires more than quick solutions. Previously, we explored the deep, very real risks AI introduces to the learning process. Risks to curiosity, to persistence, and to meaningful understanding. Yet to focus only on the dangers is to miss the profoundly transformative potential of AI when integrated thoughtfully. The question becomes: What might we gain, and how do we move forward? Dismissing AI’s potential role in education is both futile and misguided. The technology exists, students are using it, and that won’t change. The question is whether we can find ways to integrate AI that enhance rather than replace learning. For students without access to private tutors or educated parents who can help with homework, AI provides something unprecedented: personalised assistance available at any time. A student struggling with calculus at midnight can get explanations, examples, and guided practice. A student whose first language isn’t the language of instruction can get help understanding complex texts. My friend, Milena Vukasinovic, a German language professor, mentioned that some of her students have used AI this way, to genuinely understand material they found confusing, to get additional explanations from different angles, to practice concepts until they clicked. The technology also enables new forms of adaptive learning that were previously impossible at scale. An AI tutor can identify precisely where a student’s understanding breaks down, adjust explanations to different approaches, provide infinite patience, and never make a student feel stupid for asking the same question multiple times. While noting the obstacles, Milan Maric, Media Studies Professor, also sees potential. When students understand the fundamentals of film production, AI tools can help them experiment with ideas more quickly, iterate on concepts, and explore possibilities that would be prohibitively time-consuming to test manually. When students grasp the fundamentals, AI is an amplifier of knowledge, not a replacement. Suppose AI (as with previous technologies) frees educators from focusing solely on repetitive memorisation and routine problem-solving, tasks that technology can handle with ease. In that case, it opens the door to prioritising critical thinking, creativity, ethical reasoning, and distinctly human capabilities. At the same time, we shouldn’t dismiss the value of memorisation altogether; knowing foundational facts and concepts by heart helps fuel reflection, analysis, and deeper understanding. The real challenge is finding intentional ways to combine these skills, rather than hoping technology alone will transform education. Here’s the uncomfortable truth: educators, policymakers, and parents are largely improvising. We don’t have established best practices because this situation is unprecedented. We don’t have studies showing what works because AI capabilities have advanced faster than research cycles. We don’t have clear guidelines because the technology keeps changing, and what’s true about AI’s capabilities today may no longer be valid six months from now. Professor Vukasinovic said something telling: ‘It’s really hard and nobody really has a solution’. This honesty is refreshing after encountering so many confident proclamations about how to ‘solve’ AI in education. The reality is messier than the solutions being proposed. Some schools try to ban AI outright, but enforcement is nearly impossible, and students become more secretive about its use. Some teachers design ‘AI-proof’ assignments, only to find students finding new workarounds or AI capabilities expanding to handle previously safe assignment types. Some educators embrace AI fully but then struggle to distinguish between students who understand the material and those who are skilled at prompting. Oral examinations might help by requiring students to explain their reasoning in real time, demonstrating understanding through spontaneous explanation rather than produced text. But this approach is time-intensive, requires trust in professional judgment over standardised metrics, and faces resistance from educational systems obsessed with quantifiable assessment. While written tests have increasingly become exercises in recognising correct answers from multiple choices, oral exams demand genuine understanding. Yes, they involve subjective judgment, and yes, some students will complain about fairness. But the real world operates on subjective human judgment. Job interviews, professional presentations, and negotiations all require the ability to think on your feet and articulate ideas to sceptical audiences. Perhaps AI is actually forcing us back toward more rigorous, if less scalable, forms of assessment. If AI can deliver information and explanations, what’s left for teachers to do? My friend’s experience suggests the answer: everything that makes education actually work. She recognises when students have used AI not through sophisticated detection software but through human observation, noticing the mismatch between a student’s typical work and their submission, understanding which grammar concepts they have and haven’t learned, and seeing the disconnect between what they can produce and what they can explain. This kind of nuanced assessment requires human judgment that no automated system replicates. More fundamentally, she cares about whether her students actually learn German, develop their thinking abilities, and grow as people. An AI will generate whatever you ask for with equal enthusiasm, whether it’s helping you learn or helping you cheat. A teacher has an investment in students’ capacity development that no algorithm can provide.

What we might gain (if we’re intentional)

Why don’t we have good answers yet

The transformed role of teachers

Teachers also provide something increasingly precious: human attention and relationship. In a world of infinite digital content and AI assistance, the attention of a real person who notices whether you’re struggling, who adjusts explanations based on your specific confusion, who models intellectual curiosity and integrity, this becomes more valuable, not less.

But teachers need support. They need professional development around AI literacy, reasonable class sizes that allow for individual attention, institutional backing when they try new approaches, and recognition that they are navigating unprecedented challenges without clear roadmaps. Expecting teachers to solve the AI problem on their own, in addition to everything else they’re responsible for, is neither fair nor realistic.

Here’s what history teaches us about technological disruption: adaptation doesn’t happen automatically. It requires sustained effort, experimentation, willingness to fail and try again, and most importantly, time.

When calculators entered classrooms, it took years to figure out how to teach mathematics using calculators as tools while ensuring students still developed number sense and mathematical thinking. When the internet became ubiquitous, it took time to teach information literacy, source evaluation, and digital citizenship. These adaptations happened through countless small experiments by individual teachers, through curriculum development, through gradual cultural shifts in what we expected from students and education.

The same process is happening now with AI, but we’re in the early, messy phase where more questions than answers exist. Both professors have been teaching for years; they are experienced and thoughtful and admit they’re struggling to figure this out. That’s not a failure on their part but the reality of confronting a genuinely new challenge.

What gives me cautious optimism is that humans are remarkably adaptive. We’ve navigated previous technological disruptions not because we’re brilliant at predicting consequences or designing perfect solutions, but because we’re willing to keep trying, adjusting, and learning from what doesn’t work. The students who currently see AI purely as a shortcut tool will eventually encounter situations where shortcuts don’t work, where genuine understanding matters, and where they’ll need capabilities they didn’t develop. Those experiences will teach lessons that no amount of adult warnings can convey.

But this adaptation won’t happen without effort. It requires educators willing to experiment with new approaches even when they’re exhausted. It requires students willing to choose difficulty over efficiency sometimes, to trust that the struggle has value. It requires parents who reinforce the importance of genuine learning rather than just grades and credentials. It requires institutions that support innovation rather than demanding impossible guarantees that new approaches will work. It requires all of us to take this seriously, rather than either panicking about AI destroying education or dismissing concerns as technophobia.

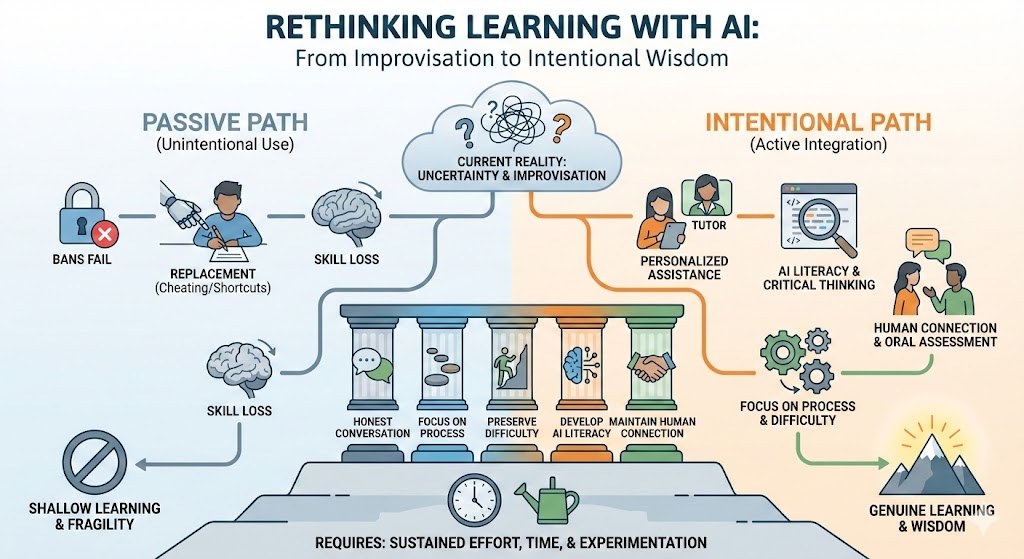

While we don’t have definitive solutions, some principles seem worth pursuing as we figure this out:

Honest conversation over prohibition: Blanket bans don’t work and drive AI use underground, where students learn nothing about responsible use. Better to acknowledge AI’s presence and have explicit discussions about when and how its use is appropriate, what counts as academic integrity, and why genuine learning matters beyond just completing assignments.

Focus on process and understanding, not just on outputs: If AI can produce polished final products, the assessment should value the journey more than the destination. This might mean requiring students to show their work and explain their reasoning, using portfolios that demonstrate growth over time, incorporating reflection where students articulate what they learned, and evaluating through conversation and presentation rather than just submitting text.

Preserve difficulty where it’s pedagogically necessary: Not every challenge should be smoothed away. Some intellectual struggle is essential for development. This might mean specific assignments done without AI assistance, certain skills practised until they become automatic, and certain knowledge that must be internalised rather than outsourced. The specifics will vary by subject, age, and context, but the principle matters: some things should remain difficult.

Develop AI literacy as a core skill: Students need to understand what AI is and isn’t, where it excels and where it fails, how to evaluate its outputs critically, when to rely on it and when to think independently. This isn’t just about AI tools but about developing the judgment to use powerful technology wisely.

Maintain human connection: In an age of increasing automation and digital mediation, the human relationships that education provides become more precious. Teachers who know their students, classrooms where students learn from each other, the social dimension of learning; these need to be protected and prioritised, not sacrificed to efficiency.

Professor Vukasinovic’s question, ‘Why do we even need this?’, deserves serious consideration. Maybe we don’t need AI in elementary education. Perhaps the costs outweigh the benefits at certain ages or in certain contexts. Maybe the optimal amount of AI in schools is less than what we currently have, not more.

But whether we ‘need’ it or not, it exists and students have access to it. The question becomes: how do we respond to this reality? Do we pretend it’s not happening? Do we attempt bans we can’t enforce? Do we give up on genuine learning and accept that education is now about managing AI tools? Or do we do the hard, uncertain work of figuring out how to preserve what matters about learning while existing in a world where AI is everywhere?

I don’t have confident answers, and I’m suspicious of anyone who does. What I do have is the conviction that the work matters. Education isn’t just about preparing workers for the economy, though that’s part of it. It’s about helping young people become thoughtful, capable, curious human beings who can navigate complexity, think independently, continue learning throughout their lives, and contribute meaningfully to society.

AI hasn’t changed these fundamental purposes. If anything, it makes them more urgent. The students currently in school will live their entire adult lives alongside AI far more capable than what we have today. They need to develop not just knowledge but judgment, not just skills but wisdom, not just the ability to use AI but the awareness of when not to.

That development requires genuine learning experiences, the kind that involve struggle, confusion, mistakes, breakthroughs, and the gradual construction of understanding. It requires adults who care enough to insist on real learning, even when shortcuts are available. It requires students willing to choose the more challenging path sometimes, to trust that the difficulty has purpose.

We will eventually adapt to AI in education. But that adaptation will not come easily or automatically. It will require sustained effort from multiple directions. Teachers experimenting with new approaches, students taking responsibility for their own learning, parents supporting genuine education over just credentials, institutions providing resources and flexibility, society valuing learning itself rather than just the certifications it produces.

The conversation about AI in education is just beginning. We need it to be honest rather than reassuring, focused on real challenges rather than theoretical solutions, and willing to admit uncertainty while still taking the problem seriously. Neither the people I spoke to nor I have the answers, but we are asking the right questions. And in the messy early stages of a profound technological shift, that might be the best we can do: Keep asking, keep trying, keep caring whether students actually learn. The answers will emerge through countless small experiments, adjustments, and discoveries. The work ahead is difficult, uncertain, and absolutely necessary.

Author: Slobodan Kovrlija